"Now it's time to present the evidence that will help the Amazon” says an internationally recognized biologist

Chris Wood is an environmental physiologist, and a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Canada and the Brazilian Academy of Science. He has been an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of British Columbia since 2012, and has been participating in expeditions in the Amazon since 1976. During his most recent trip, Wood was able to observe the impacts of a historic drought on its ecosystems.

By Tiago da Mota e Silva

Journalist | Environmental Conservation | Researcher, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA)

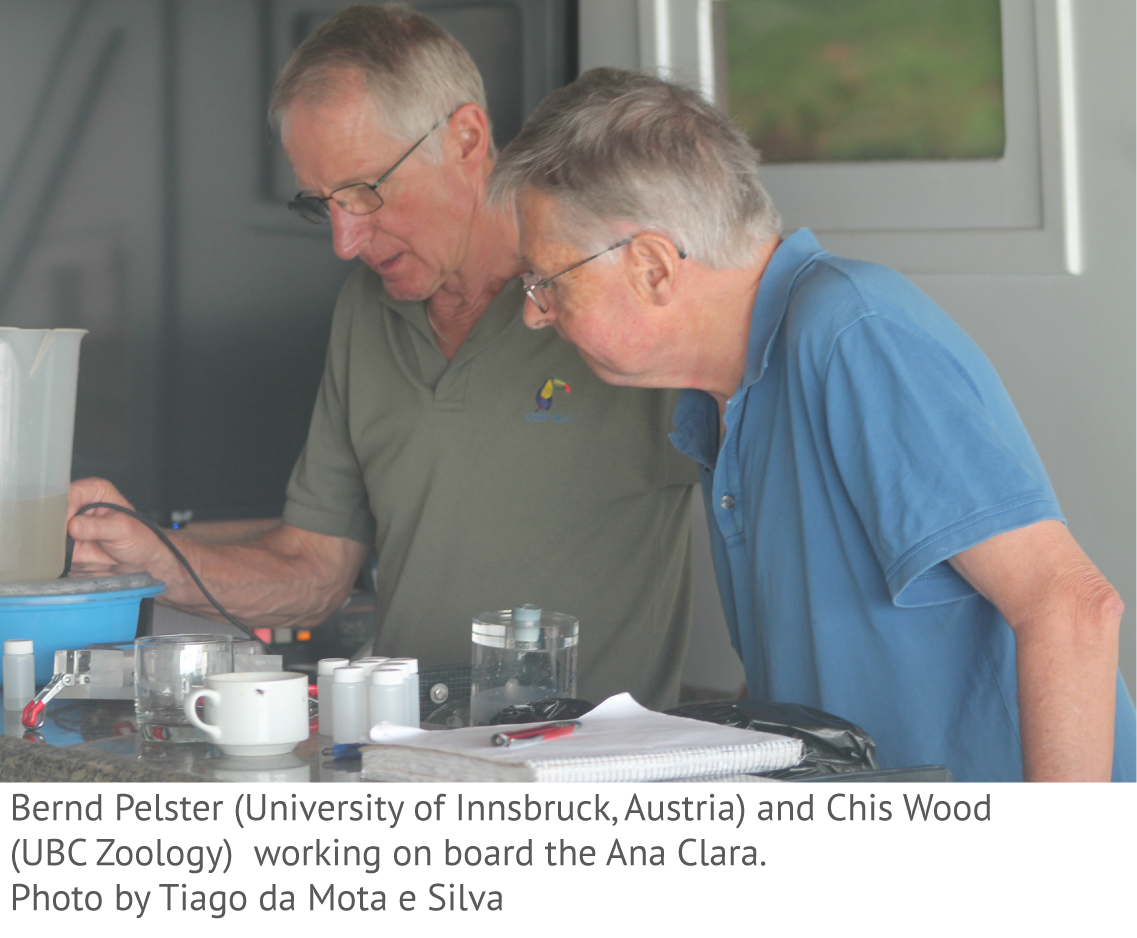

On November 21, 2023, a group of 18 scientists departed from Manaus on a boat heading into the Amazon for an expedition. Among these men and women is one of the leading experts in the study of fish physiology: Canadian biologist Chris Wood - who certainly is no stranger to such trips.

In 1976, Chris was part of the legendary Alpha Helix expedition, a boat that supported research by Europeans, North Americans, and South Americans along the rivers Negro and Solimões. Since then, Manaus has become like a second home to the researcher, who can hardly pinpoint how many times he has been there.

In addition to the Amazon, Chris has also led expeditions in North America and Africa. In each of them, he learned to adapt. "There's no perfect experiment," says Chris. So, one must adapt and improvise in the face of unforeseen circumstances. At least that's how it was at Lake Magadi in the Rift Valley of Kenya, where he turned beer bottles into respirometers, containers used to measure the oxygen consumption of a unique fish which lives there.

"For me, it all comes down to the experience of going into the field and working with animals freshly collected from nature, not those domesticated in a laboratory," explains Chris, excited to be in the Amazon.

This time, the experience is investigating the degree to which some Amazonian fish are being threatened by the higher temperatures and lower oxygen levels associated with climate change, and are being poisoned by discharges of copper. Unfortunately, concentrations of this metal above the levels established by the Brazilian National Council for the Environment (CONAMA) are being recorded, for instance, in the streams of Manaus, largely due to pollution.

Chris has a living memory of how, over time, the city of Manaus has changed and grown, and of how the Amazonian ecosystems have undergone significant transformations. This year, the region experienced the worst drought ever recorded in history, with the Rio Negro reaching historically low depths below 13 meters, according to the Manaus Port Authority.

In 2022, Chris and Brazilian scientist Adalberto Val co-authored an article predicting all sorts of difficulties for the fish in the Amazon due to climate change. However, they didn't imagine that some of their predictions would occur as soon as 2023, amidst the drought: warmer waters with less oxygen availability, for example, lead to severe losses in their populations, yet to be fully quantified.

In this interview, Chris discusses his field experiences on the seventh of 15 days of the expedition. Additionally, he shares his opinion on the current state of Brazil and research: "Now is the time for scientists to push for scholarships for students and for investments in education."

How are you feeling on the seventh day of the expedition?

I'm really thrilled to be here. It's always a fantastic adventure to undertake these research trips in the Amazon. Of course, we have the usual issues that come along with these journeys, but the research is incredibly exciting. We're seeing many fish species, and currently, we're focusing more on the amazonian catfish.

I read about a story involving you and salmon in the Bella Coola River. Looking back at the early years of your work and the experience you have now, what are the main differences?

Certainly, the questions change over time, and technology evolves too. But for me, it still boils down to the experience of taking the laboratory into the field and working with freshly collected animals in nature, not with domesticated animals that have never been in the real world. There are always those unforeseen problems you face when working in the field. Nothing works exactly as expected, so you need to adapt, change the plan. Being flexible is really important. I think the story you're referring to is when we were implanting blood flow probes into spawning salmon in the Bella Coola River and made a small enclosure with rocks to keep the fish there after quite an extensive surgery. At that time, the probes were worth quite a bit of money, probably a thousand dollars. The next morning, the fish had escaped, and there were a hundred thousand fish in that river. So, we had to scour the river up and down looking for our salmon with the probe, but we never found it. We ended up having to collect data from another fish with another probe.

So, that's an example of your improvisation skills.

I believe you always have to improvise. There's no such thing as a perfect experiment.

I imagine your improvisational skills have improved a lot over time. In this current trip you're undertaking in the Amazon, has there been any moment of improvisation?

Well, yesterday we were trying to conduct what we call CTmax studies, which involve measuring the fish's critical upper lethal temperature by placing it in a mesh container and gradually heating the water. However, the fish were escaping from our container because they were so small that they could pass through the mesh. Since we had brought some nylon stockings with us to keep various samples isolated when stored in liquid nitrogen containers, we came up with the idea of putting the stockings around the mesh container, and it worked. It's an example of a simple adaptation we can make in the field.

I read about a solution you found with beer bottles, I think...

Ah, the beer bottles! That was in Kenya. In that situation, we had no equipment because everything had been confiscated by customs authorities. We had to improvise everything. We needed respirometers that would fit these tiny two-gram fish. So, we drank the contents of those beer bottles, which proved to be the perfect size, and we were able to use them as respirometers.

Sorry, but how exactly did you empty those bottles?

With difficulty! (laughs) The first part was pretty easy, emptying the fish from the bottle is much harder. You kind of have to shake it out.

Over the years you've been visiting the Amazon, is it becoming easier to handle the unexpected or are you still surprised by different situations?

The latter. You never know what to expect. Maybe I'm a bit smarter and craftier as I get older, but it's always surprising. You don't always anticipate the problems you'll face. But for me, that's one of the great joys of doing research, solving problems in the moment.

We're experiencing this exceptional dry season, the most severe of all. From your perspective, just observing things and being here, are the changes noticeable? What has caught your attention?

Certainly, the extent of the exposed coastline of the river grabs a lot of my attention. But what really struck me was walking through the INPA [National Institutes of Research of the Amazon] campus and seeing how many trees are dead or dying in the woods. That was quite shocking to me because I've been on the campus so many times over the years, and it has always been a very healthy and wild environment. Now we're seeing all these dead trees... it's really quite disturbing. Already here on the Rio Negro, I can see that the water levels are very low. Adalberto Val and I wrote an article last year, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, where we predicted what would happen. What we expected to happen slowly is happening rapidly, like with this drought. It's so devastating... We never really thought, when we wrote it, that we'd see this the following year.

Can you recall any comparable moment to this?

Absolutely not. I was here, maybe in 2009, when the river was exceptionally high, and Manaus flooded. But I've never seen the water level this low.

There's a lot of discussion about how the Amazon is changing as it approaches some tipping points. I know these points are another tough discussion...

It's hard to know where the tipping point is, or how much deforestation will cause a collapse in the entire system. We've seen estimates between 20% and 40% deforestation. I'm not an expert on this, but I suspect we're very, very close to that.

From your perspective, what have been the strong indicators that we're undergoing a mutation in the Amazonian ecosystems as we approach these potential points?

In his laboratory, Adalberto Val relies on these climate change chambers. What they do is monitor carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and temperature in the jungle, then send this information in real time to the lab, adding additional amounts of CO2 and temperature in a controlled environment, simulating the future of climate changes and their effects on organisms, using different IPCC scenarios. The levels of CO2 captured by the equipment in the forest have been increasing over time, and this is real evidence of the climate changes happening here, likely related to forest burning. There are also many satellite photos through which we can see that many roads leaving Manaus have settlements. So, as humans encroach on the forest, they're evidently burning and destroying vegetation. And that's another clear evidence that the Amazon is undergoing mutations.

Main photo, Lake Prato in November 2019. Detail photo, same lake in Anavilhanas in November 2023, during a historical dorught.

Photos by Arvo Tuvikene

Do fish help tell this story?

That's a good question, and I don't think I have the full answer. We know, for example, what levels of metals may be dangerous to fish, and we also know that the levels of metals recorded in many streams around Manaus greatly exceed toxicity levels. There is also strong evidence of human-induced transformation in these animals. So, the fish, I believe, could tell part of the story of changes related to human actions in the Amazon.

Understanding these changes and with all the experience you've accumulated over the years, what do you think should be prioritized in your field of work in terms of investigating Amazonian ecosystems? What are the questions that still intrigue you?

I still believe that biodiversity in the Amazon is understudied. We need to understand much more about it. And we also need to understand much more about the impacts generated by humans in the Amazon, mainly the impacts of hydroelectric dams need to be studied, mining, especially illegal mining, and also the issue of the lack of sewage treatment in Manaus. I think research is needed to demonstrate to what extent these activities have negative impacts so that we can perhaps exert political pressure to implement sewage treatment, stop illegal mining, and halt the construction of new hydroelectric dams. These are things that we suspect are truly detrimental to the Amazon, but we need strong evidence in that regard. I think Brazil now has a government that is sympathetic to science. I am more hopeful. During the earlier governments of the present administration, I've seen how science has benefited progressively, by visiting universities and laboratories, observing how much money was invested in science in the country. Now, I think Brazil is back with a science and environment-friendly government, so now it's time to present the evidence that helps the Amazon.

Is it a good time to seek funding for science and develop new projects in the Amazon?

Yes, I think it is. The present Brazilian government is trying to undo the damage caused over the last four years, but it still has to deal with many constraints. But I also believe there's a sense of beginning to support science again. So now is the time for scientists to push for scholarships for students and for investments in education. However, the expectations shouldn't be too high in the short term because the present government must address a multitude of issues.

The effects of the drought in the Anavilhanas Archipelago on the Rio Negro

Photo by Tiago da Mota e Silva