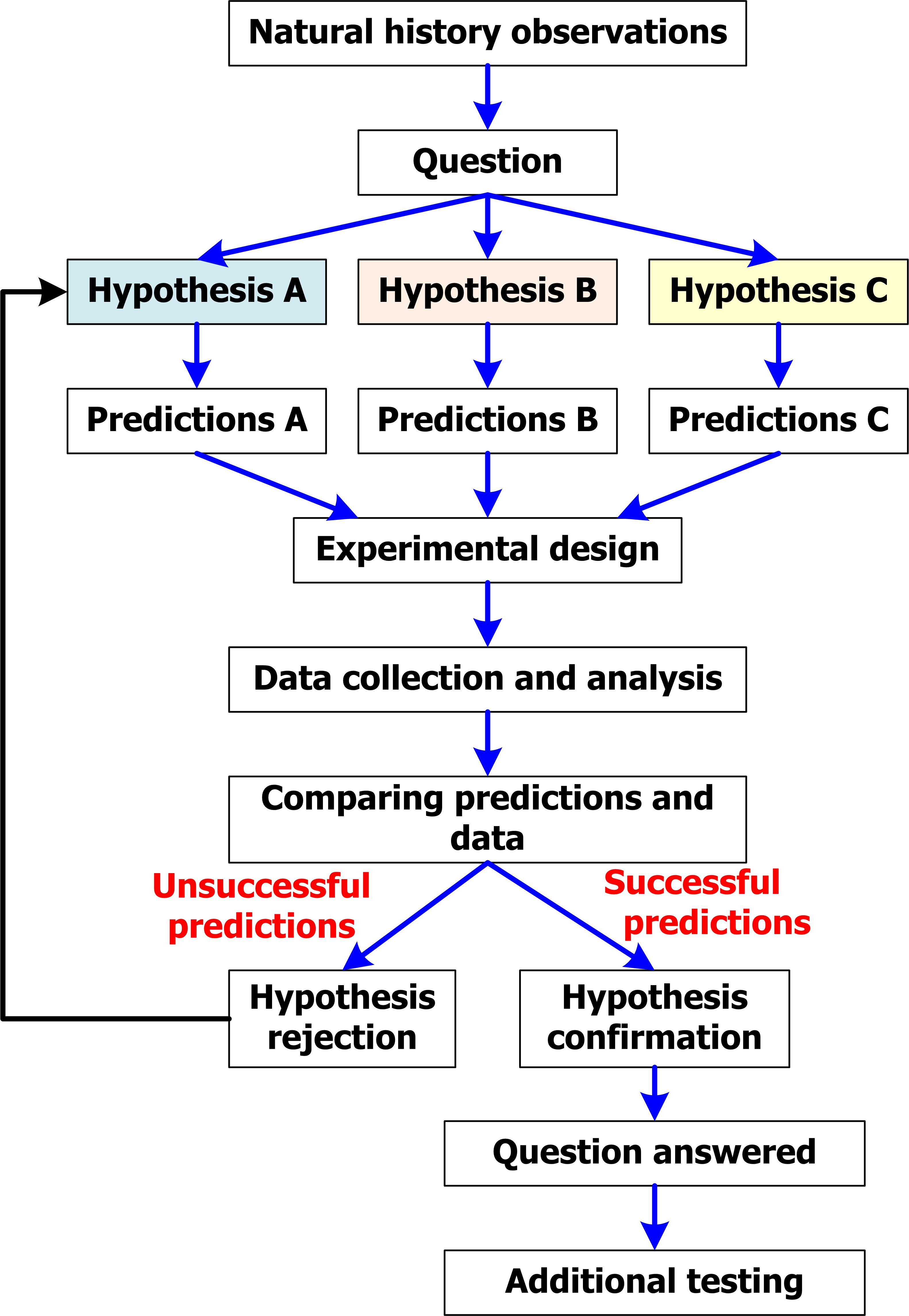

In 1897 Chamberlin wrote an article in the Journal of Geology on the method of multiple working hypotheses as a way of experimentally testing scientific ideas (Chamberlin 1897 reprinted in Science). Ecology was scarcely invented at that time and this has stimulated my quest here to see if current ecology journals subscribe to Chamberlin’s approach to science. Platt (1964) formalized this approach as “strong inference” and argued that it was the best way for science to progress rapidly. If this is the case (and some do not agree that this approach is suitable for ecology) then we might use this model to check now and then on the state of ecology via published papers.

I did a very small survey in the Journal of Animal Ecology for 2015. Most ecologists I hope would classify this as one of our leading journals. I asked the simple question of whether in the Introduction to each paper there were explicit hypotheses stated and explicit alternative hypotheses, and categorized each paper as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. There is certainly a problem here in that many papers stated a hypothesis or idea they wanted to investigate but never discussed what the alternative was, or indeed if there was an alternative hypothesis. As a potential set of covariates, I tallied how many times the word ‘hypothesis’ or ‘hypotheses’ occurred in each paper, as well as the word ‘test’, ‘prediction’, and ‘model’. Most ‘model’ and ‘test’ words were used in the context of statistical models or statistical tests of significance. Singular and plural forms of these words were all counted.

This is not a publication and I did not want to spend the rest of my life looking at all the other ecology journals and many issues, so I concentrated on the Journal of Animal Ecology, volume 84, issues 1 and 2 in 2015. I obtained these results for the 51 articles in these two issues: (number of times the word appeared per article, averaged over all articles)

| Explicit hypothesis and alternative hypotheses |

“Hypothesis” |

“Test” |

“Prediction” |

“Model” |

||

|

Yes |

22% |

Mean |

3.1 |

7.9 |

6.5 |

32.5 |

|

No |

78% |

Median |

1 |

6 |

4 |

20 |

|

No. articles |

51 |

Range |

0-23 |

0-37 |

0-27 |

0-163 |

There are lots of problems with a simple analysis like this and perhaps its utility may lie in stimulating a more sophisticated analysis of a wider variety of journals. It is certainly not a random sample of the ecology literature. But maybe it gives us a few insights into ecology 2015.

I found the results quite surprising in that many papers failed Platt’s Test for strong inference. Many papers stated hypotheses but failed to state alternative hypotheses. In some cases the implied alternative hypothesis is the now-discredited null hypothesis (Johnson 2002). One possible reason for the failure to state hypotheses clearly was discussed by Medawar many years ago (Howitt and Wilson 2014; Medawar 1963). He pointed out that most scientific papers were written backwards, analysing the data, finding out what it concluded, and then writing the introduction to the paper knowing the results to follow. A significant number of papers in these issues I have looked at here seem to have been written following Medawar’s “fraud model”.

But make of such data as you will, and I appreciate that many people write papers in a less formal style than Medawar or Platt would prefer. And many have alternative hypotheses in mind but do not write them down clearly. And perhaps many referees do not think we should be restricted to using the hypothetical deductive approach to science. All of these points of view should be discussed rather than ignored. I note that some ecological journals now turn back papers that have no clear statement of a hypothesis in the introduction to the submitted paper.

The word ‘model’ is the most common word to appear in this analysis, typically in the case of a statistical model evaluated by AIC kinds of statistics. And the word ‘test’ was most commonly used in statistical tests (‘t-test’) in a paper. Indeed virtually all of these paper overflow with statistical estimates of various kinds. Few however come back in the conclusions to state exactly what progress has been made by their paper and even less make statements about what should be done next. From this small survey there is considerable room for improvement in ecological publications.

Chamberlin, T.C. 1897. The method of multiple working hypotheses. Journal of Geology 5: 837-848 (reprinted in Science 148: 754-759 in 1965). doi:10.1126/science.148.3671.754

Howitt, S.M., and Wilson, A.N. 2014. Revisiting “Is the scientific paper a fraud?”. EMBO reports 15(5): 481-484. doi:10.1002/embr.201338302

Johnson, D.H. (2002) The role of hypothesis testing in wildlife science. Journal of Wildlife Management 66(2): 272-276. doi: 10.2307/3803159

Medawar, P.B. 1963. Is the scientific paper a fraud? In “The Threat and the Glory”. Edited by P.B. Medawar. Harper Collins, New York. pp. 228-233. (Reprinted by Harper Collins in 1990. ISBN: 9780060391126.)

Platt, J.R. 1964. Strong inference. Science 146: 347-353. doi:10.1126/science.146.3642.347