I begin with a quote from Seddon et al. (2016):

“By 2012, the consensus view based on 20 years of research was that (i) experimental reduction in species richness, at any trophic level, negatively impacts both the magnitude and stability of ecosystem functioning [12,52], and (ii) the impact of biodiversity loss on ecosystem functioning is comparable in magnitude to other major drivers of global change [13,54].”

The references are to Cardinale et al. (2012), Naeem et al. (2012), Hooper et al. (2012), and Tilman et al. (2012).

The basic conclusion of the literature cited here is that with very extensive biodiversity loss, ecosystem function such as primary productivity will be reduced. I first of all wonder which set of ecologists would doubt this. Secondly, I would like to see these papers analysed for problems of data analysis and interpretation. A good project for a graduate class in experimental design and analysis. Many of the studies I suspect are so artificial in design as to be useless for telling us what will really happen as natural biodiversity is lost. At best perhaps we can view them as political ecology to try to convince politicians and the public to do something about the true drivers of the mess, climate change and overpopulation.

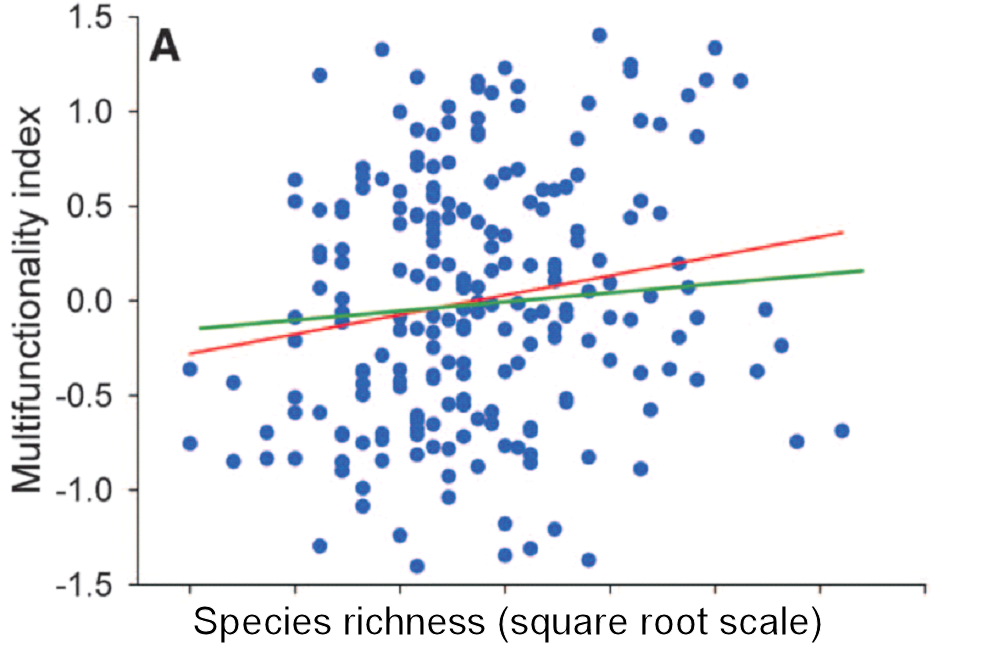

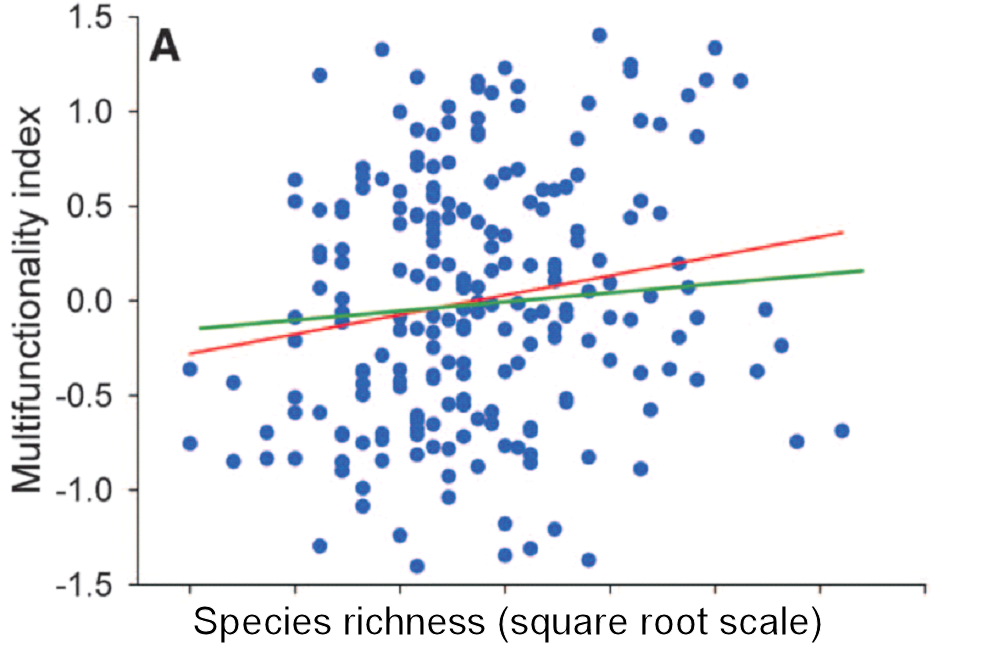

Too many of the graphs I see in published papers on biodiversity and ecosystem function look like this (from Maestre et al. (2012): data from 224 global dryland plots)

There is a trend in these data but zero predictability. And even if you feel that showing trends are good enough in ecology, the trend is very weak.

Many of these analyses utilize meta-analysis. I am a critic of the philosophy of meta-analysis and not alone in wondering how useful many of these are in guiding ecological research (Vetter et al. 2013, Koricheva, and Gurevitch 2014). Perhaps the strongest division in deciding the utility of these meta-analyses is whether one is interested in general trends across ecosystems or predictability which depends largely on understanding the mechanisms behind particular trends.

Another interesting aspect of many of these analyses lies in the preoccupation with stability as a critical ecosystem function maintained by species richness. In contrast to this belief, Jacquet et al. (2016) have argued that in empirical food webs there is no simple relationship between species richness and stability, contrary to conventional theory.

Finally, another quotation from Naeem et al. (2012) which raises a critical issue on which ecologists need to focus more:

“In much of experimental ecological research, nature is seen as the complex, species-rich reference against which treatment effects are measured. In contrast, biodiversity and ecosystem functioning experiments often simply compare replicate ecosystems that differ in biodiversity, without any replicate serving as a reference to nature. Consequently, it has often been difficult to evaluate the external validity of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning research, or how its findings map onto the “real” worlds of conservation and decision making. Put another way, what light can be shed on the stewardship of nature by microbial microcosms that have no analogs in nature, or by experimental grassland studies in which some plots have, by design, no grass species? “ (page 1403)

And for those of you who are animal ecologists, the vast bulk of these studies were done on plants with none of the vertebrate browsers and grazers present. Perhaps some problems here.

Whatever one’s view of these research paradigms, no questions will be answered if we lose too much biodiversity.

Cardinale, B.J., Duffy, J.E., Gonzalez, A., Hooper, D.U., Perrings, C., Venail, P., Narwani, A., Mace, G.M., Tilman, D., Wardle, D.A., Kinzig, A.P., Daily, G.C., Loreau, M., Grace, J.B., Larigauderie, A., Srivastava, D.S. & Naeem, S. (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486, 59-67. doi: 10.1038/nature11148

Hooper, D.U., Adair, E.C., Cardinale, B.J., Byrnes, J.E.K., Hungate, B.A., Matulich, K.L., Gonzalez, A., Duffy, J.E., Gamfeldt, L. & O/’Connor, M.I. (2012) A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature, 486, 105-108. doi: 10.1038/nature11118

Jacquet, C., Moritz, C., Morissette, L., Legagneux, P., Massol, F., Archambault, P. & Gravel, D. (2016) No complexity–stability relationship in empirical ecosystems. Nature Communications, 7, 12573. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12573

Koricheva, J. & Gurevitch, J. (2014) Uses and misuses of meta-analysis in plant ecology. Journal of Ecology, 102, 828-844. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12224

Maestre, F.T. et al. (2012) Plant species richness and ecosystem multifunctionality in global drylands. Science, 335, 214-218. doi: 10.1126/science.1215442

Naeem, S., Duffy, J.E. & Zavaleta, E. (2012) The functions of biological diversity in an Age of Extinction. Science, 336, 1401.

Seddon, N., Mace, G.M., Naeem, S., Tobias, J.A., Pigot, A.L., Cavanagh, R., Mouillot, D., Vause, J. & Walpole, M. (2016) Biodiversity in the Anthropocene: prospects and policy. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283, 20162094. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2094

Tilman, D., Reich, P.B. & Isbell, F. (2012) Biodiversity impacts ecosystem productivity as much as resources, disturbance, or herbivory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 10394-10397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208240109

Vetter, D., Rücker, G. & Storch, I. (2013) Meta-analysis: A need for well-defined usage in ecology and conservation biology. Ecosphere, 4, art74. doi: 10.1890/ES13-00062.1