Congrats to PhD Candidate Libby Natola on the publication of her paper on three-species hybridization in sapsuckers!

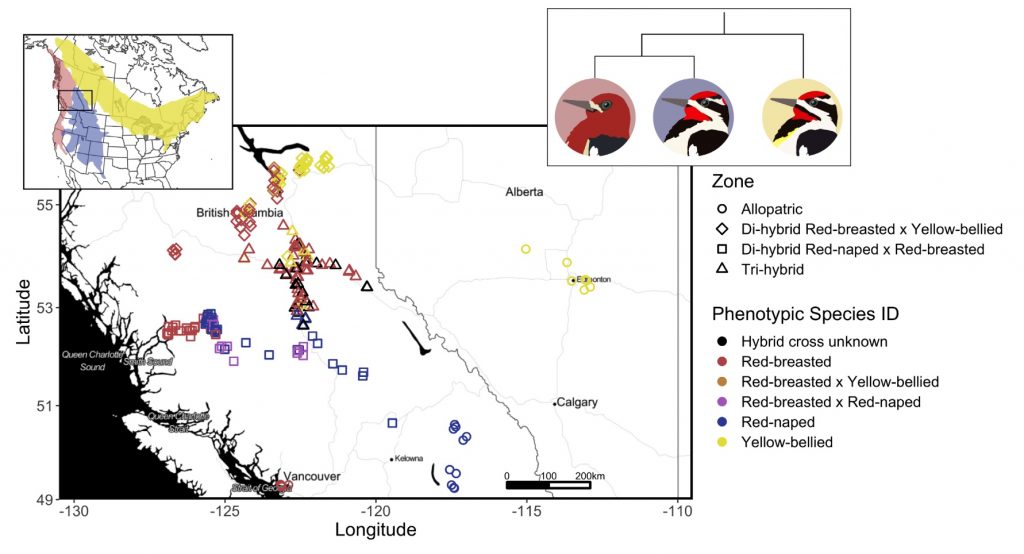

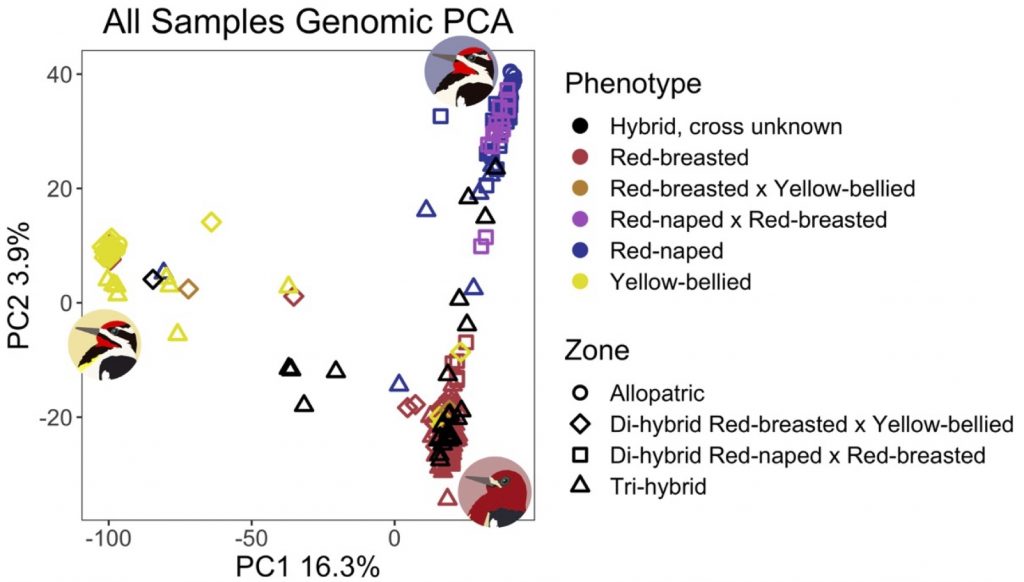

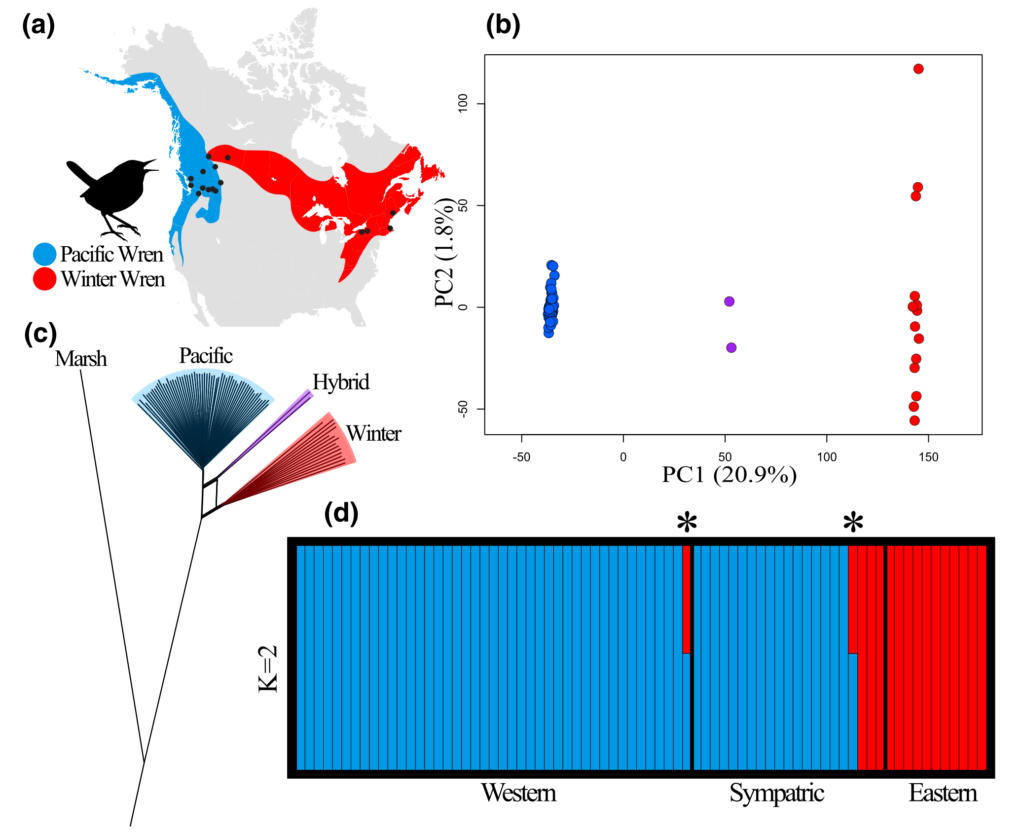

Figs.1 & 2 from the paper:

The full citation:

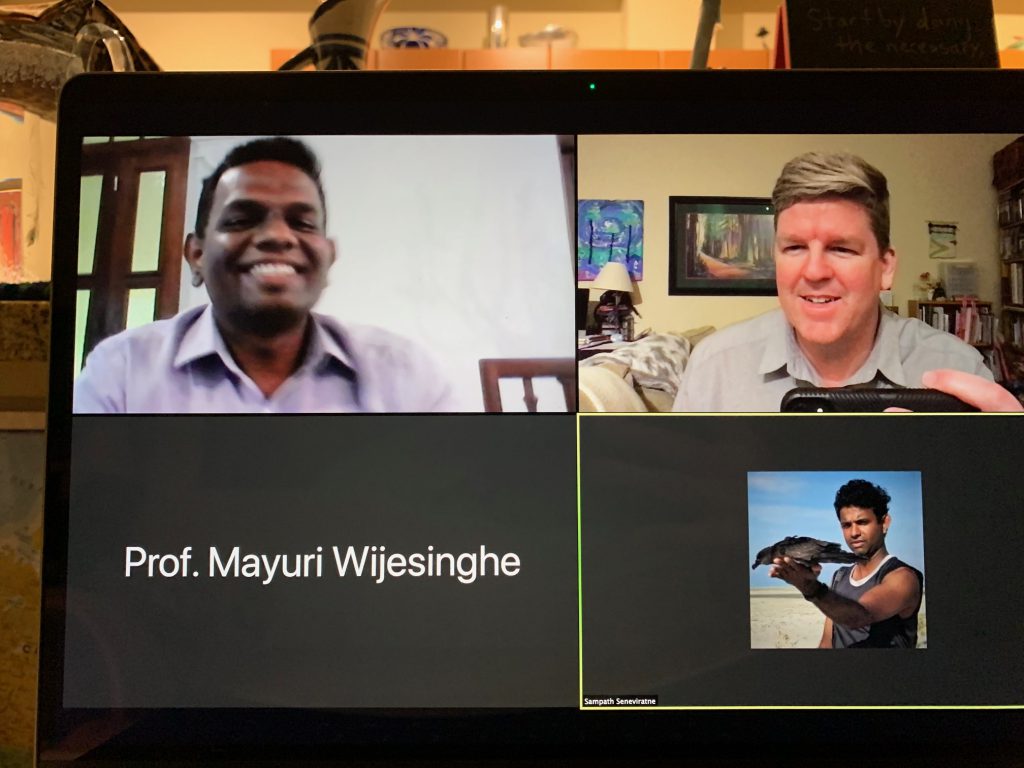

Natola, L., S.S. Seneviratne, and D. Irwin. 2022. Population genomics of an emergent tri-species hybrid zone. Molecular Ecology, early view: https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16650

(earlier version posted on bioRxiv: Link )

The abstract:

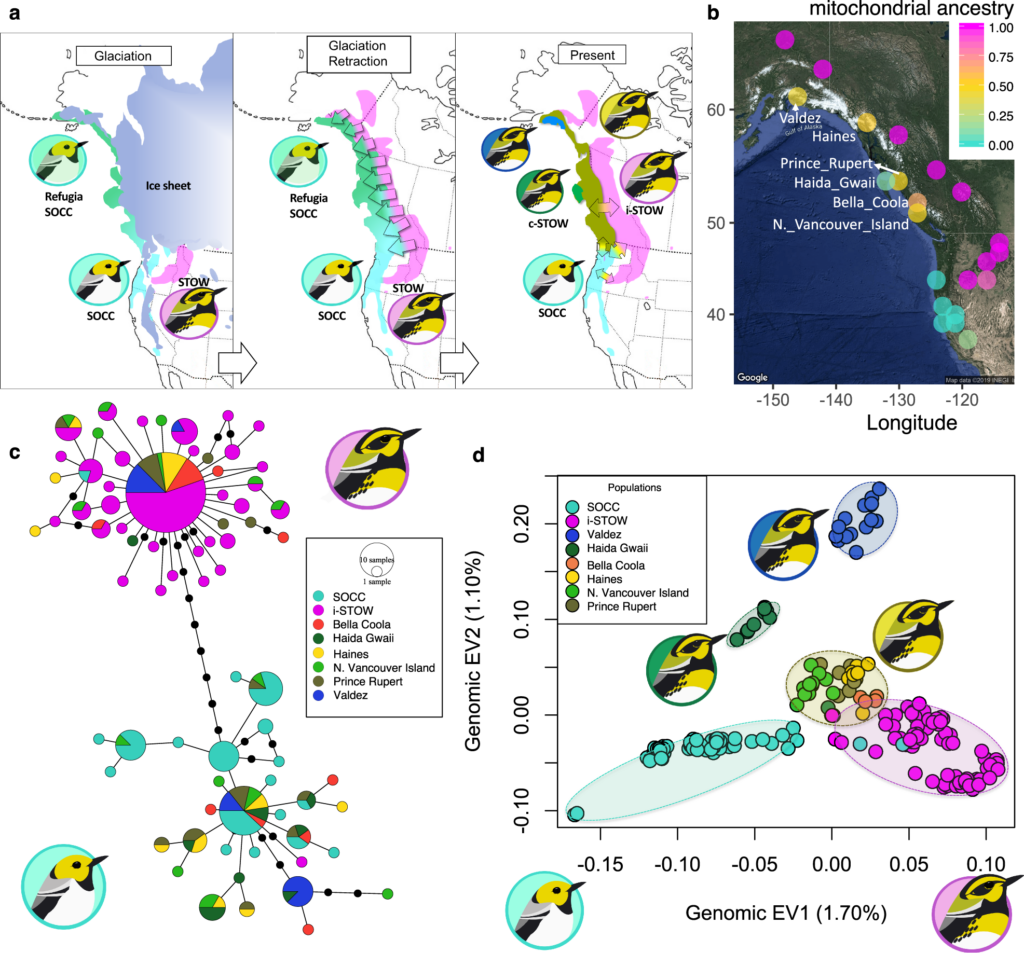

Isolating barriers that drive speciation are commonly studied in the context of two-species hybrid zones. There is however evidence that more complex introgressive relationships are common in nature. Here, we use field observations and genomic analysis, including the sequencing and assembly of a novel reference genome, to study an emergent hybrid zone involving two colliding hybrid zones of three woodpecker species: Red-breasted, Red-naped, and Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers (Sphyrapicus ruber, S. nuchalis, and S. varius). Surveys of the area surrounding Prince George, British Columbia, Canada, show that all three species are sympatric, and Genotyping-by-Sequencing identifies hybrids from each species pair and birds with ancestry from all three species. Observations of mate pair phenotypes and genotypes provide evidence for assortative mating, though there is some heterospecific pairing. Hybridization is more extensive in this tri-species hybrid zone than in two di-species hybrid zones. However, there is no evidence of a hybrid swarm and admixture is constrained to contact zones, so we classify this region as a tension zone and invoke selection against hybrids as a likely mechanism maintaining species boundaries. Analysis of sapsucker age classes does not show disadvantages in hybrid survival to adulthood, so we speculate the selection upholding the tension zone may involve hybrid fecundity. Gene flow among all sapsuckers in di-species hybrid zones suggests introgression likely occurred before the formation of this tri-species hybrid zone, and might result from bridge hybridization, vagrancies, or other three-species interactions.

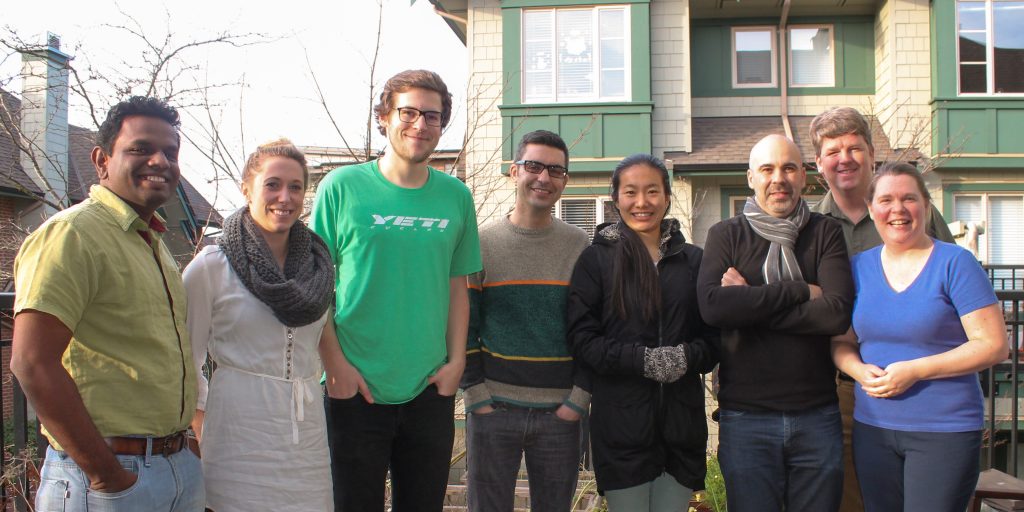

) to love birds! I think we all can learn much from these wise people.

) to love birds! I think we all can learn much from these wise people.